Blood Donation – Visual Anthropology photo essay

Dr. Luis Agote (2nd from right)

overseeing one of the first safe and effective blood transfusion in 1914. He was one

of the first to perform a non-direct blood transfusion using sodium citrate as

an anticoagulant. The first visual representation of blood transfusion and

donation served mostly medical and documentation purposes. In this picture the

process is depicted as complicated, requiring multiple people to help and also

it was needed to be recorded because it was considered a medical wonder and a

trailblazing method at the time.

Woman donating blood to the Red

Cross Blood Bank in New York City in 1943 during World War II. The traditional

idea behind blood donation is altruism and helping one’s compatriot. The first

national blood services appeared around WWII and people in the home countries

were encouraged to donate blood as a patriotic act to help their injured

soldiers. The images from around this time show a certain intimacy and

immediacy between the donor and the assistants. The purpose was clearly

propagandistic, elevating the morale and encouraging more people to donate for

the homeland. It was depicted as a small act of support that even those could

perform who did not participate in the battles.

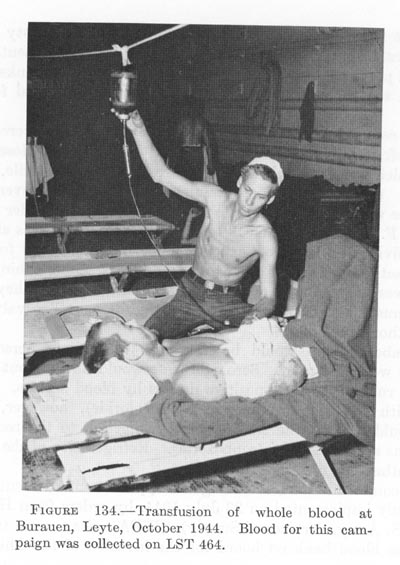

Private Roy W. Humphrey is being

given blood plasma after he was wounded by shrapnel in Sicily in August 1943.

The receiving end of donations were

also represented. Several pictures were published of wounded soldiers who

receive blood – they can be paired with the donation images as an end result of

a patriotic effort. These have the traits of the classical war photos which

show the horrors of the battles but also the heroic feats and sacrifice made by

the soldiers. It these pictures the effort is doubled: both soldiers and donors

at home make their own contributions. These photos can be understood as the

ones that set the foundation to the dominant altruism narrative in the

photography of blood donation.

In Hungary, Kazincbarcika 110

workers of the Machinist Firm participated in a blood drive for the wounded

Vietnamese soldiers in the Vietnam war on May 6, 1968. The occasion was part of

a series of events in connection with the Vietnamese solidarity month.

In the Communist era blood donation

was seen as a unifying act which not only connected compatriots within a nation

but also Communist comrades across the globe. Countries donated to each other

on a regular basis (Polish people also helped Hungarians during the 1956

Revolution). Mass donations were prevalent and expected, workers brigades did

as a “recreational activity” and received days off as a reward. These mass

blood drives were also well documented in the press to encourage other people

to join or organize such events. These photos are also utilized as a

propagandistic tool which aims to mobilize people to join the common project of

“building the Communism”.

This is a scene from a Bollywood

fiction film titled Amar Akbar Anthony (1977). After India’s

independence, as a symbolic representation of the Nehruvian nation-building

project several fiction films included scenes of voluntary, unpaid blood donation.

It was depicted as an altruistic act, making a sacrifice for a stranger or

one’s blood relatives. In this scene three identical twins who were separated

at birth and have been raised as Hindu, Muslim and Christian join forces and

donate blood to their ailing mother. She symbolizes the great Mother India and

the effort of the brothers is meant to show that despite the cultural, social

and religious differences of the country, Hindus, Muslims and Christians are

siblings who make up and can heal their nation together. The scene was also the

celebration of blood donation as a patriotic, altruistic act which should be

carried out without financial incentives. In the newly independent state the

establishment of voluntary, non-remunerated blood donation was seen as the

first step on the path of becoming a “developed”, modern state. Again, blood

donation is depicted as an altruistic act that also helps bind the newly formed

nation-state.

As the WHO guidelines state the main

cornerstone of modern healthcare is the presence of institutionalized, voluntary,

unpaid blood donation in a country. However, this system cannot always fulfill

the incredible blood hunger of most countries, especially one as enormous as

India. This photo is meant to illustrate the dangers of blood donation “with

incentives”. Occasionally, enormous competitive blood drives are organized in certain

regions of India where thousands of people participate who are often rewarded

with compensation. Among health care professionals the possibility of

contamination, breaches of hygiene regulations generate anxiety. This photo

shows the overcrowded halls, overworked phlebotomists – it is meant to generate

anxiety in the viewer who cannot be sure that all these donors can be monitored

properly to filter out pathogens in their blood. This image invokes the worse

connotations associated with the “Third World” and “developing” countries:

unregulated health care, insufficient hygiene and overcrowded spaces. It is

meant to show the risky side of blood donation which is a new theme emerging after

the heroic, patriotic and altruistic images.

This is a new instant in the history

of Indian blood donation. A woman who recovered from COVID-19 is examined by

state health care workers in Mumbai to find out if her blood plasma is suitable

for therapeutic usage for current patients. The pandemic highlighted a

different use of blood – or rather its component, blood plasma which carries

the vital antibodies that help patients in the recovery. This photo highlights

the contrast between the traditional clothing of the woman and the modern

protective gear of the health care workers – and it also meant to illustrate

that modern health care is available in every corner of the country.

Institutionalized blood management still seems synonymous with modernity and the

reliability of the Indian state which takes care of its citizens. Once again,

just like in whole blood donation, plasma donors can fulfill their patriotic

duty by helping their ill compatriots.

A Buddhist monk is donating blood in

Myanmar. Buddhist monks are enthusiastic blood donors in the country and their

fervor seems to support the image of a state with developed blood management

based on voluntary, unpaid donation. WHO is especially preoccupied with the

Southeast Asian region where this criterion of “development” cannot always be

found. However, in the country blood donation is also a practice of exclusion,

not only the basis of unity in the nation-state. The members of the Muslim

Rohingya minority are often blocked from accessing the blood banks in Rakhine

state since Buddhists insist that their blood only goes to other Buddhists and

the hospitals usually oblige (this is a hidden layer of the photo). This image

was used in the WHO official website: it is meant to show that Southeast Asian

countries have set foot on the path of “development”, of becoming more like the

Global North: they have proper, regulated blood management systems. The image

conveys order, cleanliness, safety and trust between the donor and the nurse –

it could have been taken in any Western country. It supports the narrative of a

supranational organization which advocates for “developing” and “modernizing”

the health care of countries in the Global South. As we have seen in the Indian

images, the topic of blood donation serves as a tool to explore the theme of

“development”.

Blood donation (in the form of deferral) is a practice of exclusion in other contexts as well. Being able to donate can be a form of biological citizenship, thus being permanently deferred is a symbolic banishment from the “body of the nation”. It is not closely connected to the actual act of blood donation itself, but gay and bisexual men (generally men who have sex with men) were and in many countries still are automatically excluded from blood donation. LGBT rights groups organize movements and protests for inclusion. The AIDS crisis was the first incident that turned blood donation from an altruistic act into a practice of potential danger and risk. Fear of contamination emerged and hence MSM (identified as the most prevalent risk group of HIV/AIDS) were automatically deferred. As AIDS research improved, it was revealed that MSM (who practiced safe sex and/or were in monogamous relationships) did not pose greater risk than heterosexual people who regularly have unprotected sex.

In 1996 it was revealed that blood

rations donated by Ethiopian Jews were consistently destroyed in Israel due to

the supposed HIV-risk they posed because of their African ancestry. This

discriminatory practice shed light on the larger issue of racism in the country

(which included police brutality as well). The exclusion of Ethiopian Jews from

blood donation was only eliminated in 2016 after wide-spread demonstrations.

In these previous photos blood

donation (and the right to participate in it) became a field of tensions and

conflicts as opposed to the peaceful, unifying treatment of the earlier photos.

Not everyone can become a donor and the simple practice of giving carries

symbolic meanings as well. Blood donation is not simply a medical but also a

social act, which is tied to the questions of citizenship, community and

identity. These photos also tap into this explicitly social component, while

the earlier photos mostly were concerned with the medical, biological elements.

National blood

transfusion services (like NHS in the UK and American Red Cross in the US)

started to seek more Black and Latinx blood donors to fight sickle cell disease

which is a blood disorder that impacts people of African and Latino descent more

frequently. Patients require regular blood transfusions to manage the disease

and the blood received need to match very closely which is more likely to be

achieved if the donor is of the same race or similar ethnicity – states the

website of the American Red Cross.

Here the theme of

inclusion and community return in a different context. People are encouraged to

help those “similar to themselves” with donating blood but they should do it

for their own ethnic community. It is still an act of solidarity but instead of

the wide, abstract “nation”, a more manageable, smaller community is

emphasized. It is a photo taken by the American Red Cross so it serves marketing

purposes: its aim is also to widen the donor pool and include people who are

less likely to donate (e.g. many Black and Latinx people cannot afford to miss

hours from their job or take days off just to donate).

As blood management and transfusion

techniques evolved, the separation of blood components became possible and thus

one portion of whole blood can be used more efficiently, without wasting (like

red and white cells, platelets, and plasma). Thus, one donor’s blood can help

multiple patients. Additionally, certain methods made it possible to derive blood

components separately (plasmapheresis is one, where red cells are separated

from the water and proteins upon donation and red cells are given back to the

donor, so the process is less straining). Demand for plasma grew as bleeding

and immune disorders became more prevalent in the population – also, as it

turned out the plasma of the recovered COVID-patients can help current patients

too. In the US plasma donation is paid, so it disrupts the altruistic logic of

blood donation.

In the earlier images we could see

some kind of solidarity, people having interactions (like nurses and donors).

Here the plasmapheresis machine makes the atmosphere quite medical, sterile and

impersonal. It seems a less intimate experience, the woman also seems to have

less contact with her own body, she is connected to a machine, not the blood

bag immediately. The dominant color is not red anymore, since plasma has a

golden tinge – it does not look like blood at all. This seems like the future

of blood donation – more specialized, less personal, more automated and not

fully altruistic anymore (plasma donors receive financial compensation).

Additionally, the idea of nation-maintenance has disappeared from behind the

act of blood donation – plasma donation benefits pharmaceutical companies that

use the substance as raw material for their medical products. Thus, in this

photo the donor appears not fully as a helper but as a vendor (even though the

COVID-plasma temporarily reinstated plasma donation as an altruistic act).

Megjegyzések

Megjegyzés küldése