The Truth of Intervention and Non-Intervention

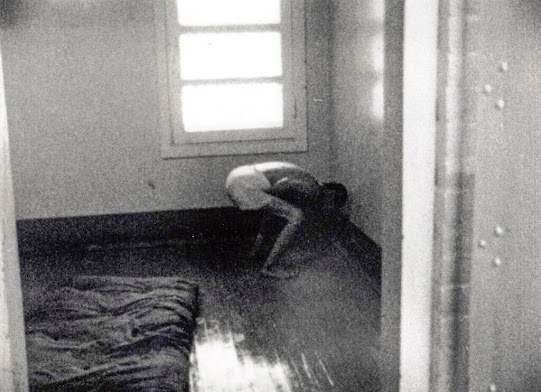

The Maysles brothers, Frederick Wiseman and David MacDougall on one side and Dziga Vertov and Abbas Kiarostami on the other. Both camps could be described as followers of the observational cinema tradition, however striking differences can be identified. As we have seen earlier, the Maysles, MacDougall and Wiseman aimed to reduce the intervention of the camera and the filmmaker to the minimum: they indeed could be seen as "flies on the wall". Obviously, this ideal is only an illusionary thing to pursue, all of them somehow transformed and affected their subjects they observed. Even if they spent weeks and months getting to know their "fields", familiarized themselves with their subjects, made friends, tried to become a natural, almost unnoticeable element of the milieu their presence was definitely noticed and probably affected the behavior of their subjects. No amount of light-weight, easily portable cameras can change this. Probably the Maysles were the most reflective about this unavoidable presence, not necessarily in the Salesman, but for example in Grey Gardens. They acted playful, sometimes provoking some reactions from their subjects to reveal something that was hidden before. They did it in a warm and respectable way - which is the polar opposite of Wiseman's cold, almost morbidly curious gaze that almost did not respect privacy (mirroring the Bridgewater guards' disregard for privacy) - a gaze that was positioned as omnipresent and omniscient, invisible and disembodied.

Vertov and Kiarostami on the other hand aim to make the camera/filmmaker itself very material and present - and also make cinematographic techniques visible. They could be considered the followers of the cinéma verité tradition. According to this school, stylization, the obvious presence of the filmmaker and the camera can actually reveal something that is hidden to the naked eye. The camera has an improved vision which shows the world in a new light (that was the main idea behind Vertov's Kino-Pravda/Film Truth theory). Intervention is inevitable and as such should be included in the final film. Interaction between the filmmaker and the subject happens anyway, why not make it explicit or even try and elicit a reaction from the subject?

In Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera and Kiarostami's Close-up the presence of the camera is used in a way to provoke reactions and dig out something that is lying behind the obvious. In Vertov's film the camera and the cinematographer is even made heroic (and sometimes funny) as they are out in the city digging out the hidden truth about everyday urban life. Before Vertov's restless, active camera mundane activities, work and leisure become the source of humor, glory and vitality. He makes these new, weird visual associations even more evident by editing and post-production work. He utilizes visual tricks (like using double exposure to enlarge and place the cinematographer in the landscape, stop motion, jump cuts) to elicit new reactions, associations and emotions in the viewer. Vertov mobilizes the original, archaic joy of cinema by celebrating movement, speed, light and texture with his camera (and by this he also celebrates the Soviet Union). The Man with a Movie Camera is also a celebration of cinema itself, merging the joy of both the Lumieres (reality-seeking/documenting the world) and Melies (fantasy-seeking/creating worlds). In his movie, technical skill and bravado is what makes reality more tangible, while in observational cinema technique was intentionally understated, some films are even decidedly "ugly" or simple because then style does not avert viewers' attention from the "reality" and the "truth".

In Kiarostami's Close-up the camera is also used in a self-reflexive way. He sometimes holds it against people as a gun to get a reaction from his subjects (like when he tries to convince the judge to let them film in the courtroom). However, in my opinion his approach is still warmer and more sensitive than that of Vertov's (more akin to the Maysles's gaze). Kiarostami is less interested in visual playfulness and trickery - he is genuinely fond of Sabzian, the poor, marginalized man with his fascination with cinema and art that makes him deceive a family. Indeed, his close-ups (as the title says) of Sabzian in the courtroom reveal something deeper about this man. The presence of the camera makes him act (play the role of the "sensitive soul" instead of the director, as the son says) but also elicits genuine feeling from him. He makes a heartfelt confession that might save him from prison. Kiarostami also recreates the impossible with the help of the camera: he records the arrest of Sabzian inside the wealthy family's house (reenacted by the original participants), but in the beginning of the film he stays outside with the taxi driver and the soldiers to follow their mundane conversation. With the help of the camera he also turns the reunion of Makhmalbaf and Sabzian into a scene worthy of a romantic movie: they emotionally hug and snuggle on a motorbike, while they ride into the sunset. But still there is nothing artificial about it, all the emotions are real. Under the facade of documenting a (quite ridiculous but also heartbreaking) trial Kiarostami's film is about filmmaking itself (he follows the self-reflexive approach of modern Iranian cinema). The power of the camera to show something more real than reality itself.

Megjegyzések

Megjegyzés küldése