Heavy Intimacy - Stéphane Breton: Eux et Moi

In Stéphane Breton's slightly uneven, very intimate documentary we can see several layers of subjectivity. First of all, it is a self-reflexive account of ethnographic field work. And secondly, he chooses to put a heavy emphasis on the subjectivity of his informants. He highlights the individuality of the village dwellers and does not refrain from showing that he has favorites among them. Anthropologists are often expected to reflect on their personal experiences, obstacles and frustrations in their field notes - but these are very personal documents that are not supposed to be shared with the public (if they are shared, it indicates a certain level of intimacy - advisors, mentors, close colleagues, friends can sometimes access them). They are simultaneously part of scholarly work and fall outside of it. Breton's film creates the impression of peeking into someone's field notes and gaining access to the otherwise hidden, awkward, uneven route which leads to the publication of a polished paper/book/documentary.

It is almost expected that anthropologists encounter difficulties during their fieldwork - if they do not, they are doing something wrong. Interlocutors should refuse to talk to them, confusion should ensue in the initial phases of exploration, misunderstandings, clashes should occur - this is the way knowledge is forged. However, the anthropologist is not supposed to complain and is expected to overcome these. It is imagined as a sort of initiation with its own stages and different levels access. Entering the field should be a dramatic experience, a sort of struggle in which the anthropologist overcomes several obstacles, makes sense of the initial chaos and interprets the network of "incomprehensible" signs. They are destined to achieve the very Western triumph of meaning making.

Challenge is always welcome, understanding and knowledge (in the Western, academic sense) should not come easy, but failure is equally unacceptable. The anthropologist cannot come home empty-handed (especially if their field trip was funded by their university or an external donor). Breton addresses all these strange contradictions. His film is so unusual because it seems to be documenting failure (or at least a very radical change of focus compared to his initial intention). Eux et moi is full of misunderstandings, confrontations and mutual exploitations from the part of the ethnographic subjects and the anthropologist. Breton records the taboos of the discipline. Even though the film shows an advanced state when Breton is already familiar with the village he is studying and already speaks the language, he reflects on his initial hardships (i.e. the locals laughed at him when he struggled with expressing himself, they refused to talk to him, they were suspicious of his true intentions). He also refrains from creating the illusion that he achieved perfect understanding with his subjects - on several occasions he rather emphasizes misunderstanding and distance as the central element of their relationship.

Breton also points out that interactions within the ethnographic fieldwork are never free of interests, power struggles and exploitation. He uses the villagers to gain knowledge (sometimes in a quite invasive way) and they use him to obtain goods (i.e. medicine, cooking oil, bush knives etc.) and cash. Even though they have their own currency system based on decorative shells, they swiftly learn how to integrate money in their network of exchange. They bargain and learn to offer the "knowledge" and information so desired by Breton by asking something in return. Eux et moi is also a document of the struggle of the villagers to integrate the "strange white man" into their social system: some refer to him as "son", some as "father", others view him as a friendly neighbor, shopkeeper or cash dispenser. Although, the villagers often make fun of him and try to trick him but it is evident that Breton holds the position of power: he has more access to money, to Western goods and useful items. He also has the opportunity to leave and return as he pleases (leaving the field and what it does to the anthropologist's subjects is always a crucial dilemma in field work).

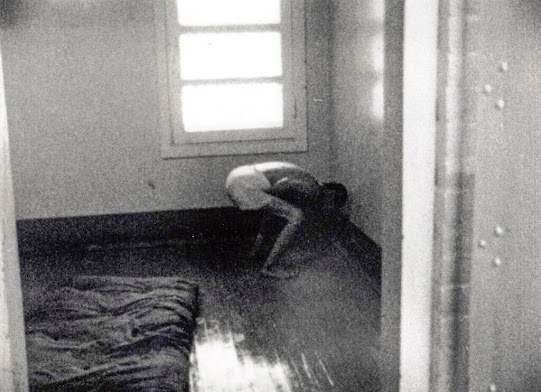

Eux et moi is also an intimate account of the relationship between the anthropologist and the ethnographic subjects. Establishing a rapport with informants is always a delicate process and academic training does not really prepare future anthropologists for this. A certain degree of intimacy is necessary but too much of it is thought to hinder (objective, neutral, professional) work. (It is a very pertinent and burning question with anthropologists of religion who are expected to understand and get very close to the religion they study, but conversion and becoming a part of a sect/cult/congregation is thought to compromise the credibility of scholarly work). Forming sexual relations with informants is almost universally deemed as immoral during field work (it is another interesting question how flirting or sex can help research, and now more and more anthropologists address sexual exploitation or rape in their writing). But how about friendship? What degree of proximity is beneficial and what is "harmful" in field work? Breton is not ashamed to show his close bonds with specific individuals (in one case, he helps pay for a young man's wife) but also reveals his clashes and conflicts with them. He expresses his frustration when they refuse to share their knowledge with him or try to cheat him. He even judges and reprimands them when they try to convince him to join in humiliating and abusing a woman who was thought to cheat on her husband. His film is very enlightening for anthropology students (among others) because it reveals hidden struggles and challenges that are often not addressed in the curriculum.

Megjegyzések

Megjegyzés küldése