Harvesting Dreams

As the COVID-pandemic was spreading across the globe and lockdown measures were introduced in almost every country, people started having weirder and more vivid dreams (which could be due to changing sleep patterns, less relaxing sleep, increased anxiety). Even those previously not interested in the esoteric or irrational, started writing dream journals and noticing their dreams more. A blog called I Dream of COVID offers a surrealist collection of strange dreams and nightmares submitted by ordinary people during the pandemic. Soon, the collective phenomenon caught the attention of researchers: Deirdre Leigh Barrett, assistant professor of psychology in Harvard Medical School started conducting a dream survey to seek patterns in people’s recent dreams and published a book titled Pandemic Dreams. She explains that collective traumas like 9/11 can also change dream patterns and give people nightmares that resemble those of post-traumatic stress disorder.

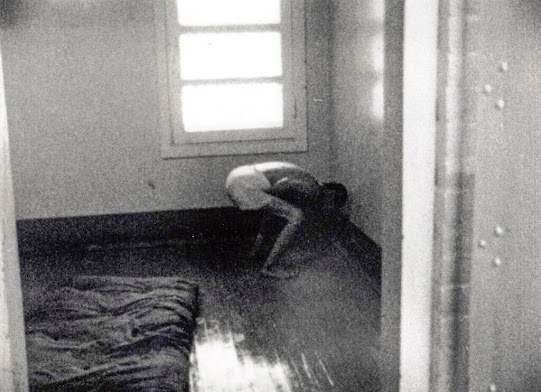

My own changing dreams and the dream accounts of my friends gave me the idea to plan a short film that collects pandemic dreams. I would select my interviewees from my university environment to capture a multi-lingual sample, since my plan is to ask them to tell me their dreams in their own languages (because people usually dream in their native languages). I would provide subtitles for the accounts – which would create a further alienating effect that mitigates the direct intimacy. The material would then “arrange” itself: as I collected and recorded all the short dream narratives, I would (arbitrarily) look for themes (if there are any) and organize them, one after the other. I will not use narration, I will let my interviewees tell their narratives freely, without my intervention. I would only use intertitles for the thematic arrangements and names, if my subjects consent to giving their names. I started shooting short visual sequences for each dream. Sometimes, the content of the specific dream would inform my choices (as a sort of free reenactment), sometimes my own feelings/associations evoked by the dream. In some cases I provide a short narrative, in others I collect a sequence of loosely related images. I intend to make each sequence unique and different since they are dreamt by a different person. One of the already visible obstacles is the lack of a quality camera. My phone's camera provides limited technical sophistication, thus the quality of the footage will not be amazing (but possibly, it could add to the blurry, dream-like quality of the eventual film).

The fact that all of my subjects would be students and researchers would give an additional layer to the narrative. It will show how the irrational occupies the realm of the rational during the pandemic, how people engaged in science have to deal with the intrusion of the subconscious into their daily lives. The film would offer a small sample of how the pandemic affects our lives and capture a glimpse of the collective, shapeless anxiety we are all going through. The personal would creep in from both sides: from the part of my "informants" whose dreams sometimes contain quite intimate and private details and on my side, since I will shoot scenes in my own immediate environment, film myself or add my own visual associations. I already shot some sequences for a nightmare with my father using the dissecting room where he works as a venue and I filmed some scenes in prominent Budapest places for a dream that involves nostalgia for the city - I provide some photos as illustration. Thus my side and my informants' side become a fusion of two types of intimacies. Starting to gather material (mainly voice recordings of the dreams in the respondents' native languages and English transcriptions for subtitles) confronted me with several revelations of intimacy. First of all, the respondents I asked to recount their dreams are my classmates and friends - I felt like a certain degree of proximity was needed if I wanted to ask them to tell me their dreams which were often strange, uncomfortable or slightly embarrassing. It added an additional layer to the process that I often had background knowledge of their lives histories and personalities, so the dreams did not just stand as simple narratives but inevitably told me something of their character (or at least I had that illusion). Another strange experience was that most of them I barely heard speak their native languages before, since in class and in social settings we mostly use English. Otherwise all of my respondents were quite enthusiastic about the project and were very open to tell me their dreams.

Megjegyzések

Megjegyzés küldése