It's Rude to Stare - Jean Rouch: Chronique d'un été

One of the most fascinating aspects of Jean Rouch's cinema is that he exposes the inherent artificiality and arbitrariness of doing ethnography. Acting like a "fly on the wall" while conducting participatory observation, expecting informants to reflect on their practices in interviews and as ethnographers making ourselves believe that we can be neutral, objective interpreters of a "culture" (let it be one that we participate/live in or one that is "alien" to us) is an illusion, or worse, self-deception. Aggravating it with holding a camera against people and expecting them to act "naturally" and being relaxed so we can record everything in a detached way is an even more severe self-deception. In Chronique d'un été (and in his other movies as well) he reveals the artifice behind ethnographic practice and shows how blurry the line is between documentary and fiction as the ethnographer strives to capture the essence of a culture.

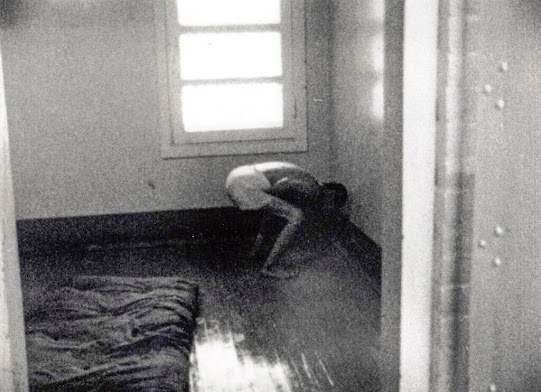

In Chronique d'un été, Rouch approached French society as he would approach a Nigerien tribe. He made the familiar seem alien by probing into the lives of Parisian people of different classes and ethnicities. He refused the principles cultivated by the filmmakers of North American observational cinema: for him simple observation proved insufficient to reveal the depths under the surface. Instead, he developed a more confrontational, provocative method of filming. Since the camera's intrusive presence is impossible to ignore, Rouch made it the central tenet of his films. Just like Dziga Vertov elevated his camera to the main role, Rouch turned it into the catalyst of the creative process. However, he devoted a bigger role to the filmmaker/ethnographer themselves by putting them in an active, inquisitive position (Vertov kept the cameraperson as an "operator", the camera with its perfect, mechanical eye was doing most of the work). In Chronique d'un été is was sometimes painful to watch as Rouch colleague, Edgar Morin pushed his informants to share very personal and disturbing details of their lives. The tone of the film fluctuates because the camera's presence occasionally pushes situations to a humorous, disturbing, uncomfortable or satirical direction. This open intervention keeps the plot in motion and pushed it to evolve. It is not Vertov's mechanical eye whose improved vision reveals intricacies of everyday life but an intrusive eye that stares at its subjects directly but invites them to stare back and interact with it.

Rouch understands the inherent violence of visually studying the other and turns the gaze back at the observer. He addresses the violence of the colonial gaze by openly discussing the struggles of independence in the former colonies (Algeria and Congo) and putting in dialogue the citizens of a colonist society with the colonized. Rouch makes it evident that meanings are very much tied to the context and it makes it difficult to understand the other (colonizer and colonized, worker and intellectual, French and foreigner etc.). We can see the struggle of dialogue in the exchange of the black student, Landry and the worker; in the discussion about the camp tattoo between the Holocaust-survivor Marceline and the African university students and the painful, intimate conversation between Mary Lou and Morin. However, he does not give up entirely on mutual understanding - his camera also symbolizes this optimism by not only intruding and provoking but listening deeply to its subjects. Rouch challenges his actors but he gazes at them lovingly and never judges anything they say. Rouch also adopts the intellectual, self-reflexive playfulness of the French nouvelle vague (which also owes to Vertov's self-reflexivity) by criticizing and destabilizing the confident, seemingly omniscient colonial gaze. Landry, the black student acts as an amateur anthropologist commenting sarcastically on the curious customs of French people. The people on the street are often astonished by his strange questions and inquisitive gaze that defamiliarizes the practices, values and customs they deem self-evident. They feel they are allowed to stare (they turn after Landry and the white French girl who walks beside him) but find it rude to be stared at. Rouch also elegantly lets go of forcing one interpretation on his own film. This is shown nicely in his gesture of screening the film to his subjects and prompting them to discuss it afterwards. In the closing sequence, him and Morin summarize the discussion and express their frustration that some of the participants did not see the characters as lovable as they intended to present them. Eventually, they acknowledge that it is impossible to control the reactions of the audience; once the film is made public, it is up to the viewers to interpret it.

Megjegyzések

Megjegyzés küldése