Flaherty and the Innocent Eye in Nanook

I think the idea or rather ideal of the 'innocent eye' quite important when talking about Flaherty's Nanook of the North. It has been the Holy Grail of classical anthropologists: to see a "culture", a group of people and their practices as they are, in their pure form and convey them in such a way for their (white, middle class, Western) readers - who were often fellow researchers. However, as a parallel intention, they were trying hard to prove their familiarity with their object of inquiry which was the cornerstone of their professional aptness. Their account of the object had to demonstrate that the anthropologist had spent sufficient time in the original environment and gained insight which surpasses even that of the "native" - because it is innocent and analytical at the same time; situated inside and outside simultaneously.

I found a lot of intriguing ambivalences in Flaherty's film. First of all, he seems to be aiming for this effect of the 'innocent eye' while also emphasizing his familiarity with the Inuit culture (i.e. how he lived with them, was dependent on them). He seems to be having this archaic aim of preservation prevalent in early ethnography: he is recording a culture which is disappearing. His 'trickery' and acts of 'staging' (which blurs the line of documentary and fiction in Nanook) stem from this anxiety over disappearance: he re-enacts 'ancient' Inuit techniques (like the long abandoned, dangerous walrus hunting with harpoons) just to capture what is disappearing.

Despite his quite outdated, romanticized approach, he touches on very contemporary dilemmas as well. In certain bits, Flaherty captures the Inuit-Canadian interrelations that change Nanook's way of life (and in this sense Flaherty contradicts himself because he seems to claim that the Inuit people have an 'unchanging, stagnant, primitive' way of life but in the episode of the 'white trader' he actually shows certain cultural influences which have a transformative effect on Inuit culture and show that their practices in fact are capable of change, as every other culture (like using knives or guns for hunting). Flaherty is anxious about the disruptive influence of 'white men' on pure, intact Inuit culture and the unequal power relations between them but plays the episode of the white trader for jokes (he makes Nanook look ridiculous as he engages with the phonograph) but he seems less conscious about his unequal power dynamics with Nanook in the process of filmmaking.

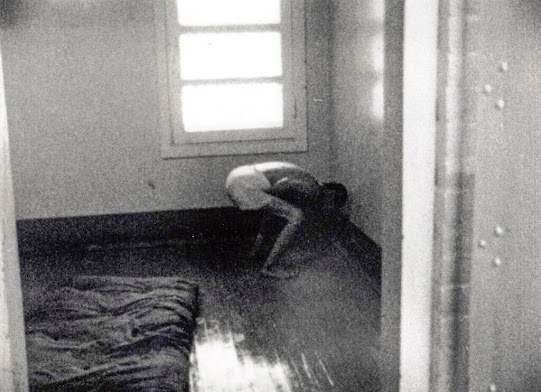

Additionally, there is the question of ethics. Nanook and his family is an active collaborator in the making of the film: they reproduce certain abandoned techniques for Flaherty, build a fake igloo with a wall missing so the sun can provide enough light for filming. They are accomplices in the 'staging' and fictionalization of their own culture and life story. However, Flaherty still uses them for his own aims, presents them as 'noble savages', kin with the animals they hunt for survival (as Rothman in his article about the film points out as well). Flaherty makes his presence as a filmmaker unreflected, stages 'innocence' and non-participation while he in fact has a profound effect on the people he is recording (like when he doesn't help them by shooting the walrus, just to capture the stages moment of ancient harpoon-based hunting).

Megjegyzések

Megjegyzés küldése