Fascinating Bodies - Representations of the Nuba by Leni Riefenstahl and Trinh T. Minh-Ha

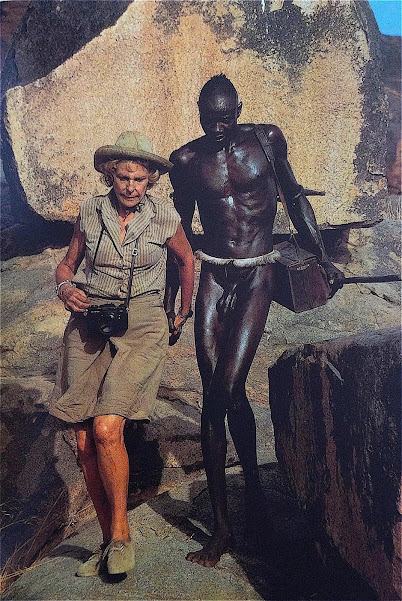

Comparing the representations of Leni Riefenstahl and Trinh T. Minh-Ha about the Nuba people raises very old and still unsolved dilemmas in anthropology. According to Susan Sontag Riefenstahl as a photographer still utilizes aesthetic choices and techniques that she developed in the Nazi era. She presents the Nuba as mere statuesque bodies, exceptional athletes and pleasing textures. This infatuation with beauty and perfection seems to echo the Nazi devotion with physical flawlessness which was deeply connected to the subordination and extermination of other bodies which were deemed "uglier", "weaker" or simply marked as different. However, Trinh T. Minh-Ha in Reassemblage aims to represent the Nuba in their societal context, with flaws, in the rhythm of the everyday - an intentionally tries to avoid the compulsive meaning-making endeavour of Western anthropologists. Instead, in her film she places the deconstruction of the Western anthropological tradition in the center, juxtaposing her critical narration and rhythmic sequences of the everyday activities of the Nuba. In the case of both authors the knowledge of their previous work and background add to the array of potential interpretations. Riefenstahl was a known supporter of Hitler, friend to many leaders of the Third Reich. As a documentary filmmaker she promoted the glory of the regime and helped spread its fame in Western countries. Trinh T. Minh-Ha on the other hand, is a known feminist and postcolonial critic of the Western anthropological tradition, in her writing style, approach and methods she aims to point out the biases and distorting effects of this seemingly universal paradigm. I believe that the question whether we should separate the artist from art could also be formulated as 'should we separate the researcher from the research itself'? And then we can find another point where Trinh T. Minh-Ha and Riefenstahl could be compared or rather brought into conversation.

I also found Trinh T. Minh-Ha's Reassemblage quite confusing, but I think this feeling partially stemmed from the intentionally and radically subversive form she used which went against the conventional ethnographic mode of representation. She refused to "create a narrative" (as opposed to Riefenstahl), so she left the viewer quite lost amidst the swirl of images and sounds which were up to our own interpretation (in her book chapter she criticized the compulsion of anthropologists to categorize, analyze and interpret everything and offer a clear-cut explanation to the reader). However, she created one narrative (or at least part of it) about herself as an ethnographer making the film. I believe this is what made her approach very different from that of Riefenstahl, her radical self-reflection (after all "her relation to the topic" is what she can grasp with more confidence and security than the "mind of the native") and her absolute refusal to create a linear, pretty interpretation. It was also fascinating how she used representations of the body in a radically different way than Riefenstahl. It seems that the German filmmaker has an almost bisexual fascination with the bodies of men and women alike (which is paradoxically asexual and deeply sensual at the same time). She objectifies them, rips them out of their context, while Trinh T. Minh-Ha also devotes significant screen time to naked bodies but treats them as natural and part of a wider societal matrix. She often uses close ups of breasts but presents them in their diversity and as a non-sexualized, natural body part that nurtures and nourishes (she also seems to act against the dominant Western scopic regime that posits women's breasts as inherently sexual). Her Nuba bodies are diverse and often flawed.

Megjegyzések

Megjegyzés küldése