Carnivores - Forest of Bliss and Leviathan

We have already discussed the notion and the possibility of an 'innocent eye' regarding Flaherty's Nanook. In that film there was a curious tension between the filmmaker's intention of depicting the "fearless, lovable, happy-go-lucky Eskimo" and his tampering with the apparent pro-filmic reality. Flaherty set up a fake half-igloo in order to get enough sunlight and place his enormous camera in order to capture the sleeping Inuit family. He forced Nanook and his crew to hunt walrus with atavistic harpoons, just to catch a whiff of archaic, unchanging air of the old Inuit ways. He very much altered the "reality" he intended to preserve on film - we can argue if his method is ethnographically acceptable or not.

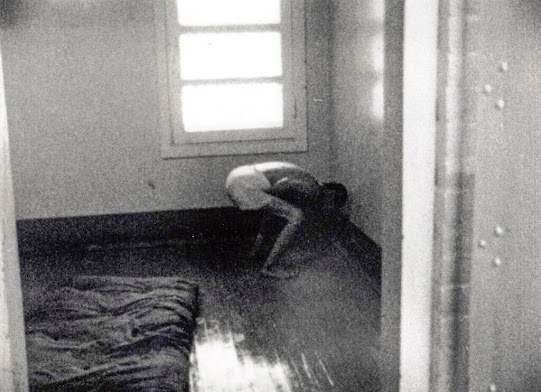

In his essay Weinberger points out that in visual ethnographic circles, 'art' and 'aesthetics' are curse words. They stand against the neutrality and objectivity of 'reality' and 'science'. Technical bravado, beauty and visual pleasure stand in the way of 'knowledge production' and cognition. Hence, it is thought that 'real' ethnographic films are made with pronouncedly understated technical skills, graininess, damaged, faulty visuals. There is an intriguing tension in Forest of Bliss (Robert Gardner) and Leviathan (Lucian Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel). On one hand - on the surface level - they seem to cultivate this archaic ethnographic desire of the innocent eye that reveals - without mediation or intervention - the totality of a phenomenon. As an additional advantage, they do not utilize explanatory narration, they do not shape or influence the judgments of the viewers. However, many critics among anthropologists accused them of being too 'aesthetic': they get seduced by textures, the abundance of sounds, the beauty of visuals (even in the most abhorrent views). How can we learn anything from such saturated, free-flowing and direct stimuli? Where is the omniscient, sober voice of the anthropologist that guides the ignorant viewers and guards them from the overwhelming, undecipherable flow of images and sounds?

I would argue that the creators of both Forest of Bliss and Leviathan treat their viewers and subjects with respect. They do not intend to force interpretations on them or manipulate them into behaving in a certain way. They let actions happen in front of the camera and they do not turn away either from accidental beauty or obscenity. Viewers need to decipher the meanings behind the rich, complex system of signs that operate behind both a common US fishing boat and the funeral rituals of Benares. They do not act like they have all the answers and explanations. It is no secret that this level of deep observation and immersion was made possible by the more portable and less invasive cameras that were not at the disposal of Flaherty or Vertov.

But it is also not completely true that the filmmakers do not interfere or apply certain frames of interpretation on the subjects they film. In both movies there is a vague, almost transcendental, mythological lens that organizes the seemingly unedited, random material. The boats of Benares float in the mist with their dead cargo like Charon's boat and the Massachusetts fishing trawler becomes the mythical monster of Leviathan itself. These grand, all-encompassing(?) themes help orient the viewer (needless to note that these are primarily Western frames). The creators invite the viewer to receive the movies rather sensually than rationally, they present a flurry of images and sounds - the beautiful and aesthetically pleasing mixes with the ugly and disturbing. Sounds sometimes hurt and sometimes caress the ears. They simultaneously offer a view that would be available for a non-anthropologist layperson who was present in Benares or on the boat but also peek into the depths that would never be reachable for the viewers. It is the cunning mix of Flaherty's innocent eye, the non-interventionist observational cinema of Wiseman and the Maysles and Vertov's highly technical and mediated gaze that offers a more 'perfect' view than the regular human eye. Moreover, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel venture into the terrain of collaborative filmmaking when they equip their fisherman subjects with portable cameras that can be attached to their bodies while they work.

Megjegyzések

Megjegyzés küldése